Steps Between | Christine Kirouac – Creative Residency

January 27 2024 / 10:00am – April 3 2024 / 5:00pm

The exhibition The Recipe Project by Winnipeg-based Métis artist/writer Christine Kirouac is presented in CVAG’s South Gallery from January 27 – March 23. Through her residency Steps Between, the artist’s ongoing creative inquiry and explorations extend the conversations instigated by her installed work at the gallery.

Christine will be writing a combination of prose, memoir pieces, and prompts for visitors around the act of drawing writing, processes of transcription, stories of the five women in the gallery, their choices, and her growing interpretations of The Recipe Project.

——————————————

February 1, 2024

The tip of my pencil is a snail drawing its body across a piece of geography, its viscous underbelly recording every edge of ground gravel, moss spore and shard of trash. My drawings are not surrogates for photographs. They are not copies of a fleeting moment captured by a camera, what would be the point of that failed exercise in repetition? I first transcribe a template of lines, a complex and indecipherable topography. I use the pencil to traverse as a snail would, drawing and pulling itself from point “A” towards point “B”. There is no other option for me. I never finish a drawing, a drawing ends and I was a part of it.

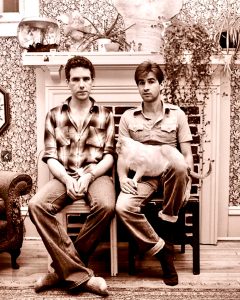

IMAGE: (bottom left) courtesy of Larry Glawson

Beatrice

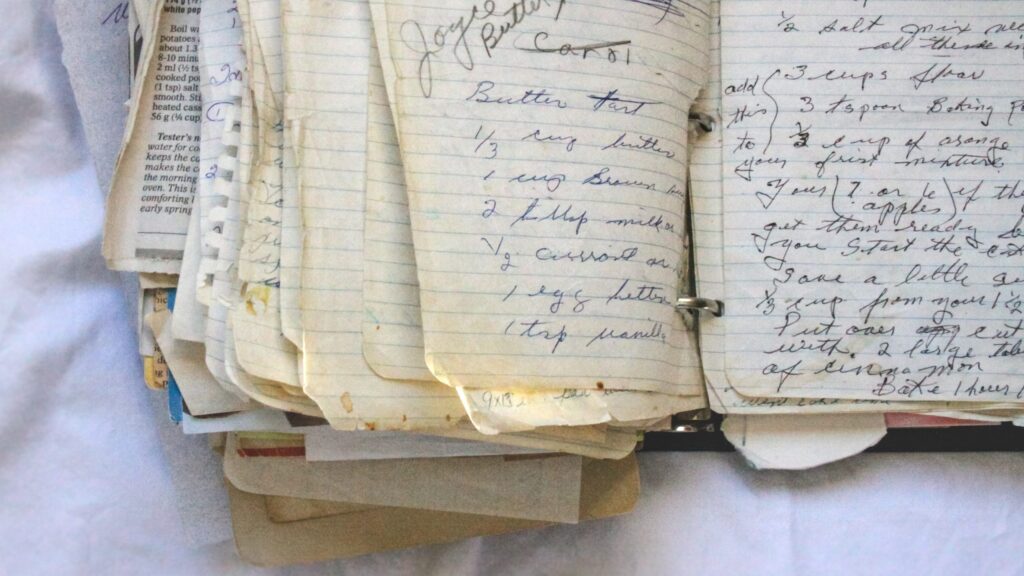

I have never met Beatrice, but I know her son. We were curated together in a photography exhibition in the early nineties, mine a black and white image of a naked male model with slides of my family home life projected onto his skin. Beside it, a self portrait of Larry and his young lover Doug sitting in two chairs set up in front of a fireplace, a cat is about to leap from one lap to the other. They are young, in their sock feet and aware of their beauty and promise. Larry has now consciously removed himself from the art world, disillusioned and tired of the competition. He lives mostly in a time suspended sameness of day to day in the apartment, and revels in it. He and Doug have now shared their lives for forty-five years and are contently amused by the play of their Siamese cats Riley and Betty, and the daily baking of deliciously warm and flaky things. His favorite thing to bake are butter tarts. “My family has craved my mom’s butter tarts since I was born and now her great grandchildren crave them. She didn’t teach me, but I think of her every time I make my own.”

And so over pancakes and over-easy eggs at the Nook, he spoke of her. The small Manitoba town she grew up in. Her French Canadian upbringing. We talked about the daring films of French Director Gaspe Noe and the never-ending slog of being and staying an artist.

“As I remember it, she didn’t pick those portrait totem items, I did based on the objects I equated with the home she grew up in that were different from what I knew, (chamber pot, pitcher and ashtray). As a young adult in the 50s she was a heavy smoker, like most people she knew then. The standing ashtray was featured in pretty much every house I went into and there were lots of comparisons of the various styles and details; the handles, the feet, the color and size of the glass ashtray and whether it had a lighter built in or not. Smoking really was a lifestyle and my mom was a glamorous smoker (at least I thought so).”

My own father was a heavy smoker. I understood and remember it as a part of him. The weighty colored glass ashtray on the coffee table. Ours was midnight blue and after mom would scrub the ash from the thick bottom and hold it up to the sun from the kitchen window. The whole world took on the ultramarine of deep mysterious water.

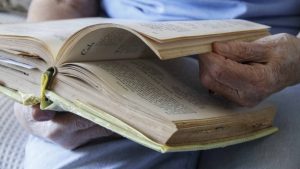

Ruth

“She’s fading,” my friend said. A slow folding in on herself into an origami stone. She is in a wheelchair all the hours she is awake. Polio. She has to choreograph her index finger and thumb to pinch the page corner of her book to turn it, or lift her fine crystal sherry glass with two hands to minimize the tremors, the one etched with irises, to her lips like a chalice.

I stand on the dining room table and unhook each crystal teardrop one by one, then track her shaking hand as she reaches for it. There is a system, two bowls with warm water. One with mild soap, and one to rinse. There are dozens of crystals on the family chandelier that hangs above the dining room table. I pass her the tear drop, she dips it in soapy water, then the rinse bowl and dries it with a soft thread bare tea towel. She passes it back and I unhook another. We do this every four months or so, the sun always tattling on the chandelier, showing the slightest dust within the dangling and paling rainbow prisms. The observance of maintenance, like applying her lipstick, keeping and making hair appointments, though she rarely goes out. It is the knowing it was tended to and will need to be again, that settles her.

These rituals somehow organize her future. We alternate the same cleaning of her silver tea service, hallmarked 1900 London. Her mother used it daily when hosting lunch for the teachers from her school. But like many beautiful and useful objects, it’s usefulness has made its transition in tense from present to past. An inanimate thing in the china cabinet that despite its lack of function, must still be ‘maintained’ to keep its luster and appeal, its purpose now to ‘be’ beautiful sitting beside the oval wedding serving plate with the rose pattern, behind glass.

When Language Seeks Its Other: Drawing Writing | Writing Drawings

When I draw other people’s words, a few things happen at once: the various interpretations of meaning of the words being drawn, and the formal language of curves, shapes and lines themselves. Repetitive and recognizable loops linking one thought to the next, curves trailing off into negative space or abruptly stopping like a regret. When I draw other people’s words I think about forgery, defined in the dictionary as: “The action of forging or producing a copy of a document, signature, banknote, or work of art.” In my case, the forgery is the ‘work of art’ itself. My intentions are not deceitful, I am not designating myself as that person, but rather exercising an attempt in inhabitation.

I write in my ‘mother’s hand’ notes from her to myself. It is comforting. It teaches me something I can’t define about her. The roundness of some letters like body parts I can see on myself, the backswing of a capital ‘I’. A seemingly benign message such as Good Morning Oatmeal Ready; Notes My Mother Left Me takes on new significance or closeness when I slowly retrace her letters that I have almost memorized kinetically just from having seen the same sentences over many years. I don’t need to read the words to know what they say. I sense the ease and speed of her sentiment in that moment as I try to mimic the perfect roundness of a hastily written ‘O’. Listened to enough times, even an improvisational jazz recording can be mastered, although whether it should be is another question. I knew that whether I wanted it or not, oatmeal had been made and that that morning was good.

At some point in my life I resigned myself to the way I wrote cursive, or printed, whether I like the shape of my letters or the incomplete way I always treat my ‘R’s and ‘H’s, aware that I am never quite committing fully to them. There is something final in that resignation, that I never will.

The Story of the First Goose

Traditional Métis Roasted Goose is Lenore’s response to my funeral food prompt. Made when she was young, growing up in Birch River Manitoba and geese hunting was done in season. I created the image of Lenore’s father (my grandfather) walking through the tall grasses, warm and limp geese swinging from their necks in his fists. The swaying weight lengthening his stride towards the little house and a waiting fire.

On Christmas of 2021, Lenore and I ordered a goose from the local butcher in Victoria. This goose would ‘be’ more, than ‘be’ eaten. Cooking fowl, as anyone who has knows, requires several stages of preparing and roasting. We had to start early taking turns pricking its raw puckered skin all over with a large-eyed sewing needle to let the rich fat flow out. We removed the giblets but left the wing tips, as I could see the left one had somehow turned down at a right angle at the end and punctured its own body. It came that way. The fleshy nub, or pope’s nose, was not bothersome to either of us. It was roasted in the oven with celery, carrots, the innards and potatoes in the morning and then rested in a nest of washed up kelp and driftwood at the sea’s edge that afternoon. Through drawing, these oceanic elements took on the appearance of things that could bind and feed. Kelp became slick verdant umbilical cords and thick braids of Manila sailing rope; wet and dark mahogany driftwood became writhing black snakes. Free from the domestication of the kitchen, Lenore’s funeral food choice was back soaring along the horizon line between sky and sea.

The Story of the Second Goose

I caught sight of a dead Canada Goose on the gravel shoulder of Bishop Grandin Highway in Winnipeg. I thought I would have to wait for a hunter to shoot one for me in the late fall, but there she was, Lenore’s goose, like a half full sandbag lying on its side. I could see the confused faces of passing drivers through their windshields as I gently picked her up and began walking down the grassy median towards my car. She was dead but not bleeding. I gently pressed her feather layers against me, her legs beating against my thighs as I strode, her flaccid black neck draped over my forearm. She was the size of a toddler and as heavy. Where was her life partner watching from? I hoped he could continue South knowing her migration was not over.

I had periodically been looking for recycled brass at the scrap metal depot, and as I was doubled over the side of a giant bin of discarded ornamental deer, penguins, bent candle holders, engraved plates and squished bowls, the scrap attendant standing behind me said, “I cast brass things in my yard.” I said I wanted to cast two Canada Goose wings in brass and was looking for scrap pieces that could melt in a small crucible. He said he makes brass knuckles and belt buckles mostly, but had two dead Canada geese in his freezer. “They kept landing in my yard and hissing at the dog,” he yelled over the crushing machinery in the background. “I made sure I shot them both, they mate for life, you know, didn’t want to leave one without the other.”

I laid her on a black plastic bag in the trunk. Once home in the yard, I removed her wings, roughly and quickly with a sharp knife before she started to smell. I laid the detached wings and body on the grass and smudged with a bundle of sage, sweetgrass and tobacco. I dug a hole by the back fence beside the holes I had dug for a dead crow and hummingbird earlier that summer. The large quill feathers held to the wings so strongly I had to use pliers to release them, as I ripped at the down it floated all around me like a soft snowfall. I made a fire in the pit and singed the fine pin hairs off the bald wings, then roasted the two zed shaped bones in the oven on a pan with tinfoil. I imagined this process is what my Métis grandparents would have done, what Métis still do today.

Peter Lorre

Years ago, I was having lunch with a friend at Cafe Zoetrope in San Francisco, owned by Director Francis Ford Coppola. The waitress was young and bronzed. She brought us two glasses of Pinot Grigio and I said, “Oh, I’m sorry, we didn’t order these.” She responded with a slight smile, “Courtesy of Mr. Coppola, Ms. Shue.” I didn’t correct her. I have been mistaken for actress Elizabeth Shue on several occasions during the nineties. I can’t put my finger on why we look alike, maybe it is as simple as where our features had settled in that second a picture is taken. I think facial features get scrambled before every photograph. In any case, it was enough to get free wine from Frank’s vineyard. I thanked the waitress and held the glass up to cheer the man behind the bar with a thick dark hair, round glasses and a solid beard like a Lego building block had been snapped onto his chin. I assumed that was him, I could have been wrong, but so was he.

On FB today, The Shuttle of Music (a group I don’t know) posted a happy 83rd birthday message to activist and musician Buffy Saint-Marie. The picture of her was serious and sexy with lots of turquoise jewelry that popped against the black background and her still black hair. She looked like what is collectively understood as the proud, strong modern Indian confronting the camera straight on. It came out recently that she was never of the Cree descent she claimed, but had either believed herself to be, convinced herself she had become Cree through a ceremonial anointing of sorts, or decided being Indian would advance her career in ways nothing else could. Out of curiosity I checked and as many people clicked laugh emojis as love and like emojis, I clicked neither. The line has been drawn, but rather than choosing between two polar reactions, I am more interested in the whispered secrets we tell ourselves when we look in the mirror.

My birth mother and I were looking through childhood pictures of each other. She was looking for likenesses between us and I was searching for how different we were. She doesn’t have many baby pictures she said, and of those that remain, mostly are of her and her fraternal twin sister in the forties and fifties, always side by side, dressed in the same handmade outfits, with distracted poses and impatient expressions that children tend to have when they are told to stop for a picture. I picked up a rare one of just her off the table, a close up, her eyes puffy and shut to the sun shining in her face; it came off as a grimace. “You look like Peter Lorre here,” I said. She laughed, “Do I?” I pulled up some Google images, looking for one of the film noir actor that most resembled Lenore’s baby face or one where Lenore looked most like Peter Lorre in that moment. Maybe it is the flood of light in both black and white images washing out the details until all that is left is a Halloween pumpkin with two eyes, a nose and mouth. In Fritz Lang’s 1931 film M, a twenty-seven year old Lorre plays a serial child killer, tormented by his own sick desires. He was often described by critics as having a ‘babyface’, moon pie shaped and soft with full lips. His character is barely seen in the first half of the film, yet he is the subject as the entire plot follows the struggle of this small German town to discover his true identity.

The image I chose to compare to Lenore’s is from the scene where Peter Lorre’s character is staring into a shop window, at a mirror on the other side of the glass. As he is studying his own psyche in his reflection, the mirror shows him a young girl of perhaps eight, unsuspectingly sitting on a bench behind him, alone. We watch his face move through the tortuous phases as he attempts to control a want he desperately doesn’t want to want. Maybe it is his ability to convey all this, using only his eyes that allows the viewer to see the human behind the killer. Or maybe its nothing and I’m fabricating the whole thing, but for a split second sitting in her high chair, I could have sworn my birth mother had the wide set somnolent eyes of Peter Lorre.

I had been dating a beautiful man with doughy tummy and long black kinky hair. I loved him I think, the cadence of his voice made my knees melt. He broke up with me upon returning from a vacation he took alone to Newfoundland, and I was having trouble imagining that he could live without what I thought we had between us. I turned to a comfort I had before, not remembering if it helped or not, watching The Lord of the Rings repeatedly. I remember how Kate Blanchett’s voice soothed me. Like a booming cinematic whisper entering my body from all directions. I watched that movie many times back to back after he broke it to me. I took that picture then, the one I thought closest to Elizabeth Shue’s playfully pretending to be caught braless in a meadow of marguerites by the photographer. I faked my smile, I like to think in that moment she did too.

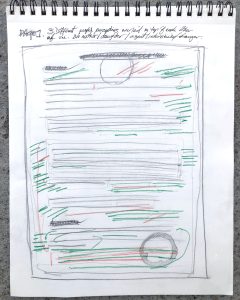

Adoption Abstract: Page 1 & 2

Adoption Abstract is loaded with content, perceptions and interpretations from three people who did not know each other, over three different time frames: 1968, when the interview between agency counselor and my birth mother took place; 1994, when I received this document in the mail after registering with the adoption agency as an adult; and 2023, when I asked my birth mother to respond to the content in the letter. After Lenore and I added our responses, notes and thoughts to the margins and spaces of the original document, I did two sketches of this information as an abstract drawing of lines, to consider it visually without content. Each line of drawn green, red, blue or black data is a type of ‘asemic’ phrasing of my own making, a language I can read and comprehend, like discovering animal shapes in clouds. In my drawings, the act of slowly leaking information, whether it be words or colored shapes, is a trust in abstraction where in the end an whole image or idea emerges, albeit still open-ended in what it might mean to a viewer.

Both in the Letters & Cards and Adoption Abstract my birth mother’s handwriting is that of a stranger with an occasional familiarity I observe in the random flow from the suffix to the following prefix of her words. She demonstrates the swollen belly of a small case ‘g’ or ‘y’ that we both share. I notice we both switch from writing a printed ‘s’ to a cursive ‘s’ in the midst of a word without care or concern. We both leave our lowercase ‘a’s and ‘o’s open could suggest a precariousness of character. Her ‘E’s are always capitalized, even in the middle or at the end of a word. Her writing is neater than mine, prettier, as though it were being judged on those merits. When I asked her to respond to the original documents for the drawing Adoption Abstract, I encouraged her to make notes anywhere, running over top of the text if it pleased her to, maybe as an emotive gesture of frustration or even anger. “I can’t write messy, even if I tried,” she said. “That isn’t me.”

Montana

I don’t know how to bead, how to bite birch bark, tan hides or embroider beautiful moccasins. I leave these things to other artists devoted to keeping Indigenous traditions from ever being eradicated again. These are not the things I am drawn to when I think about having to be Métis. I did not grow up in the cultures of my biological parents, Métis and Irish. I was French Canadian as soon as I was adopted, and lived in a home that spoke French, around the smell of tortierre and maple sugar pie. I never remember feeling that I was missing a ‘way of living’ in my body. I was not a ‘Sixties Scoop’ baby, stolen from my mother’s homestead. Could my Indian heritage being unknown to me, be a stand-in for my biological mother and father being unknown to me?

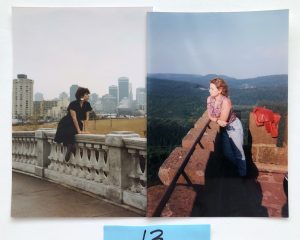

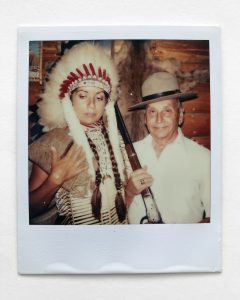

Last year, my birth mother showed me four Polaroids of herself in her early thirties, standing in a rustic log cabin. They had the syrupy saturated color of the seventies, pumped up and unreal. She is wearing a War Bonnet in the Polaroids and cradling a rifle in her arms. The photos still smelled of developer chemicals. In one she is standing beside an older white man in a ranger’s hat with a rigid brim. It is tilted. Lenore is noticeably taller than him even without the War Bonnet and he is holding a rifle.

Lenore told me a story about a man she dated once, not really dated as much as traveled to Montana where he lived when he asked her to. He was a coroner and mortician because the town he lived in was small, and one person had to be both. One of his responsibilities was to scatter the ashes of the deceased when there was no next of kin. The coroner would take containers of people up in his Cessna plane and do the business of releasing people to the wind.

This one day, the business for that week had to be done and the flying weather was agreeable, so Lenore went with him. After they had climbed to the appropriate height, he yelled at her to open the door. “What?!” she yelled back. “You are going to have to do it!” he shouted. He didn’t have his co-pilot this time, and so the deed fell to her. She waddled low over to the door and threw all her weight into sliding it open, the wind immediately sucking out her sun hat. “That’s it! Just toss him out!” I wondered if he knew anything more about this person about to be a bird, other than what he learned performing the autopsy. How did he die? Why was he so alone at the end that a young stranger would be the one to handle his remains? Gripping the door with one hand and crouching to keep her gravity low, Lenore edged the large coffee can towards her with one foot, she didn’t want to become the bird. “Do I have to open the can?” she called. “Of course!” he yelled even harder. “Do it now or I’ll have to circle back!” She held the man in the can between her knees and pried the rubber lid off. She thought she should say something profound, something about god or the spiritual world, but the noise and the wind wouldn’t let it come. So she said a quick dinner grace under her breath and lifted the can opening to the gaping hole in the side of the plane.

Yesterday, Lenore and I were looking at photo albums and there again were the Polaroids of her in the headdress. Her bare arms sharing the same warm sienna color of the great logs lining the interior of the cabin. The rifle resting in her arms. “Who took this photo?” I asked, surprised to realize there must have been another person in the room. “The mortician!” she said, surprised to have remembered. Up to then, her Métis(ness) had only been suspected as she and her twin sister grew up around other brown faces in Birch River. She said her and her fraternal twin sister had always carried an incognito presence, an ancient strain around in their bones since childhood, but nobody in the family dared claim or name it.

The mortician/coroner took her to visit his friend the park ranger, at his office in a log cabin. When she stepped from the blinding sun into the dark cool office that doubled as a local historical museum, she remembers being awe struck by all the Indigenous regalia hanging on the walls and in that very moment, having a question suddenly answered. Her Indian roared up inside her. Did she ask the ranger if she could put on one of the many headdresses? Or did he suggest it to her? Or did the mortician take one off the wall and tease her with it? She can’t recall only that when she put it on, she knew. The coolness and comfort of the gun metal against her warm arms, the heft of the eagle feathers on her head and running down her back. The gravity of these objects established her stance. Did she ask to be photographed? Or did the coroner/mortician want to memorialize his pretty little Pocahontas for his own pleasure?

Years later, she would verify our Cree, Irish, Métis and Shoshone heritage. Our lineage of women who would wear the men’s warrior headdresses after they returned from war, a traditional act of self respect and the women’s collective strength. She looked in the wonky tin mirror on the wall the ranger used for shaving. Her face still dusted with the grey ash of the remains that had blown back in her face as she tried to tip the coffee can into the whipping air. As she was telling me the story, I imagined her licking two fingers on one hand and holding them apart at her cheek, making two marks in the ash. War paint. In the photo it looks as though her own braids are laying over her small chest, but she recalls her hair was short and so the human hair braids had to be attached to the piece, just underneath the two ermine pelts that hung from the headband at her temples. The hair looked very convincing as her own.

Before we finally met in person, we spent a year mailing handwritten letters back and forth intentionally without pictures (I didn’t want my ‘looks’ in any given photograph from any one moment in time to say “this is what I look like”, nor did I want to attach any sentiment to a photo of her given to me). We met in person at her friend’s home in Vancouver, a neutral place. When a middle-aged woman answered the door, I searched her face for mine, it wasn’t there. It was Helen, her friend. When Lenore came to the door, I again searched her face for mine, it wasn’t there either, not in that moment anyway. Maybe there would be a flash later down the road, I wasn’t sure.

That was thirty years ago. Until then, there seemed no visible reason to suggest I had Indian blood, no deep sensation in my body that alerted me to the ancestral spirits of a Native past yet. When I look in the mirror even now, I still see reddish blonde curly hair adverse to taming, fair skin that burns and eyes that change with my mood from green to blue or hazel and on rare occasions, grey.

She said she had never told that story about the Montana man, the ashes and the moment her nagging question was finally answered, till now. I asked her why not. She said she wasn’t sure, she would have to think about it.

Estuary

Every day I walk to the mouth where the Courtenay River meets the sea.

January 20, 2024

An older woman came down the path towards me dressed like Geraldine Chaplin in Doctor Zhivago. Lux creamy colored furs all about her small frame and head, holding the leash of her toy Manchester in front and away from her body. She stomped one foot in front and across the other to advance herself. I couldn’t tell if she was intentionally imitating a runway model, was a model or had been day drinking. She was fabulous looking and refreshing among the Gortex and sporty fleece. With a raised gay voice she addressed everyone that passed of what a beautiful day it was. I inherited my mother’s full length black mink coat, or rather I told my sister I should get it because she got my mom’s family ring when she passed. My father bought it for her as a status symbol of his success early in his career as a restauranteur. She wasn’t one who was comfortable in flamboyance, unlike my paternal grandmother who wore fur stoles like daily jewelry. He wanted her to own it, a show of his commitment to her and his ability to provide. I didn’t even know it was Christian Dior with her initials IBK embroidered in gold on the inside pocket. I only ever remember it coming out of the plastic once a year for Christmas midnight mass. I wear it around the house sometimes, naked underneath. The perfectly balanced weight of it feels like other bodies draped around me, the gentle pressure of multiple limbs. Friends warn me of the red paint throwers, but I love the way it cocoons my shape in softness and protection, the fur tips of the trim along the bottom barely brushing the floor and the high collar tickles my earlobes.

February 1, 2024

Up the path I could see a group of people all looking up. As I got closer, I looked up too. Four people held camouflage pattered cameras with long matching lenses. The estuary doubles as a bird sanctuary and the cement trail runs along side a small aircraft landing strip. The trees were still bare and appeared dead. There were six Blue Herons squatting on branches equally spaced apart, all had their backs to the watchers talking in hushed voices. The tree was high but not that wide and the gangly branches arched dramatically under the weight of bodies, Their stick legs folded up and neck and beaks slipped inside their packed feathers like a knife into its sheath.

There was another tree just down the path. Also hibernating with naked arthritic branches. It was full of pigeons, equally distributed throughout. That birds could communicate such exacting math skills made me feel foolish, gawking at them in a group of humans falling over each other just to get a glimpse or photograph of the natural perfection I myself seem so inept at achieving.

February 14, 2024

Two raccoons were copulating in the tree today. The male on top of the female, grabbing to steady himself with both clawed hands. They turned and spun around on the branch making it bend and sway precariously as the male tried to pin her down.

We all stood watching together. I visited a Douglas Gordon exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery years ago. Watching the raccoons copulate made me think of one of his video loops titled Blue. A small video monitor on the floor with the artist’s two hands visible against a white ground. The index finger on one hand begins to stroke the other hand, awakening it to slowly form a circle with his thumb and index finger that becomes a hole. His other index finger becomes aroused and straight and begins to enter the hole. I looked down watching this sex act together with a group of strangers in a semi-circle. Was I feeling a confused desire? It was just too hands, my brain knew this, but the finger pulling and pushing the skin around the hole in and out in slow motion was intellectually erotic to say the least, the eroticism of watching a sex act that wasn’t a sex act. There was no romance or sensuality, it was deliciously lewd and I felt sufficiently uncomfortable, not because of what I was watching, but because I was with other strangers watching.

We stood together looking up into the bare tree, watching the raccoons getting something necessary done. There was nothing ‘blue’ about their public display. “Look, they’re making love” an older woman said out loud to her husband (and the group of strangers, and me). The raccoons didn’t care about having an audience. Maybe she thought their act was romantic, lucky her.

The Wood That Bends

… to be continued…